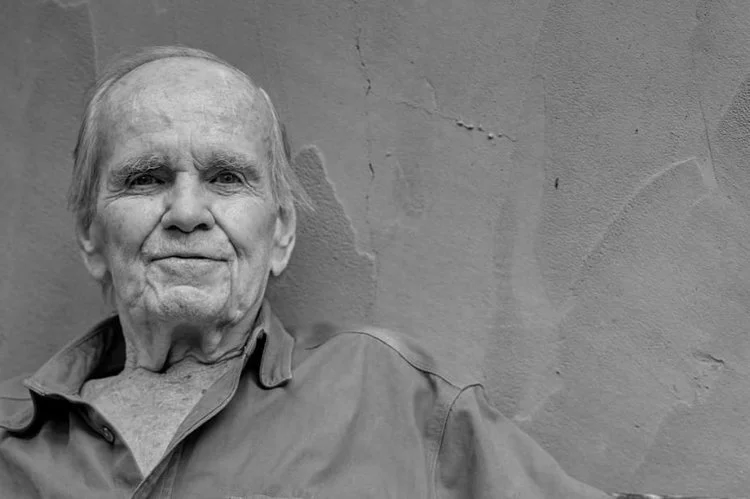

On the thirteenth of June the American writer Cormac McCarthy died.

On the thirteenth of June the American writer Cormac McCarthy died.

McCarthy was the author of fifteen works. I am re-reading The Border Trilogy

presently, and I had just concluded a weekend of discussing McCarthy’s figure of the

Judge in Blood Meridian, when on the Tuesday morning I awoke to the news of his

passing. There was a strangeness to it that has not yet gone away, a strangeness I have

not yet felt at the passing of a figure such as he, if there is any other figure such as he.

Each of McCarthy’s books constitutes a carefully constructed meditation on Justice

and Darkness in some terrifying and harrowing manner. Often I struggle to respond

when asked why I revere McCarthy’s prose so greatly, for too easily is he seen as a

writer of pure savagery. I tend to say that his sentences stand alone and for themselves

as testaments to what only he can do, but that is not always a satisfying answer. To

me, McCarthy refracted the fragility of such worn-out concepts as Good and Evil in a

world riven not by a chance hate, but rather by a deep and festering wound that is

named Man, and yet he wrote to preserve the shadows of these tributary ideals

cascading down and breaking all the while against the History of our own making. It

is this confluence of a vision of beauty as rending as it is sublime that few writers ever

achieve, and that McCarthy achieves in the scene in The Crossing whereupon the

young cowboy Billy Parham lays upon the ground the corpse of the wolf to whom he

was beholden in a contract written in a language of justice impossibly other than our

own and yet one that could be none other than it.

Upon the news of his death, I tried again to cognize the nature of his prose and thus

exactly what we have lost, and whether this lostness was perhaps always contained

there in his writings, like the trace of the coming dawn’s light so painfully rewritten

again and again throughout his novels. I do not know though that I am up to this task,

and that alone is perhaps what strikes me every time I read McCarthy: that his

language and his world are ones that we are never equal to, that we can never face up

to. Who can comprehend the Judge? Who can bear to think the carrying of the fire?

As if called to witness some tribunal at which what is on trial is our very Being, in all

its smallness and grandeur, McCarthy frames our testimony in terms that none other

could. And now that he is gone the trial continues but we are bereft of the language

with which to speak, as if a gag has now been placed in our mouth where once we had

poetry, and so our condemnation is writ large and unyielding.

By, Jamie Davies